what do the speaker and those in attendance expect to experience when the last onset occurs

A critical reading of a archetype Dickinson verse form by Dr Oliver Tearle

Expiry is a theme that looms large in the poetry of Emily Dickinson (1830-86), and perchance no more so than in the celebrated poem of hers that begins 'I heard a Wing fizz – when I died'. This is not only a poem nearly death: it's a poem about the event of expiry, the moment of dying. Below is the verse form, and a brief analysis of its language and meaning.

I heard a Wing buzz – when I died –

The Stillness in the Room

Was like the Stillness in the Air –

Between the Heaves of Storm –

The Eyes around – had wrung them dry out –

And Breaths were gathering business firm

For that concluding Onset – when the King

Be witnessed – in the Room –

I willed my Keepsakes – Signed away

What portion of me exist

Assignable – and then it was

In that location interposed a Wing –

With Blueish – uncertain – stumbling Buzz –

Between the light – and me –

Then the Windows failed – and so

I could not run into to run across –

'I heard a Fly buzz – when I died': summary

In summary, 'I heard a Fly buzz – when I died' is a verse form spoken past a dead person: note the by tense of 'died' in that commencement line. The speaker is already dead, and is telling us about what happened at her deathbed. (Nosotros say 'her' simply the speaker could well exist male – Dickinson often adopts a male person vocalization in her poems, so the point remains moot.)

And dying, one of the about momentous events in anyone's life (and certainly the last), is foregrounded in that opening line – though not as much as information technology could be. No, first we have to heard about the fly that buzzed.

The opening line, 'I heard a Fly buzz – when I died', is the opposite of bathos (that anti-climax where one starts grandly and then fizzles out, such as in Alexander Pope's historic line from The Rape of the Lock: 'Dost sometimes counsel have, and sometimes tea'): here, we first with the small – the literally pocket-size – and end with the momentous, 'died'.

Everything, we are told, was withal and silent around the speaker's deathbed. Even the mourners attending her have stopped weeping: 'The Optics around – had wrung them dry', significant 'their optics had wrung themselves dry' or 'they had wrung their eyes dry' with crying. At present'southward not the time for tears: just stillness and silence. Everyone, Dickinson'south speaker tells u.s.a., seemed braced for the moment when the speaker of the poem would die, and the 'King' would exist  'witnessed' in the room – presumably King Death, coming to have the speaker away.

'witnessed' in the room – presumably King Death, coming to have the speaker away.

The speaker had simply signed her volition doling out her 'Keepsakes' to her beneficiaries, and it was so, we are told, after her final will and testament had been signed, that the fly 'interposed' itself in the scene. 'With Blue – uncertain – stumbling Buzz' uses Dickinson's trademark dashes to great outcome, carrying the sudden, darting way flies can movement effectually a room, especially around light.

We may not have thought of such a movement as 'stumbling' (tin flying insects stumble?) and then the presence of the discussion pulls u.s. up short, makes u.s.a. stumble over Dickinson's line.

'I heard a Wing buzz – when I died': analysis

This fly comes between the speaker and 'the light'. Has she seen the lite? How should we interpret this? Is information technology simply the candle or lamp in the room lighting it (such as would attract a bluebottle to it), or is the 'light' signalling the arrival of that 'King', Death? Has he come for her?

And why then do the Windows fail, and how should we analyse that final line, 'I could not see to see'? Perhaps one clue is offered by the way nosotros talk, in the English language linguistic communication, of 'seers' and '2nd sight': seers were often blind in that they couldn't physically see, simply in another sense they saw further than everyone else because they had the souvenir of foresight and prophecy (consider Tiresias from Oedipus Male monarch). 'Second sight', similarly, is a supposed form of clairvoyance whereby the gifted person has admission to an invisible world – the earth beyond death, for instance.

Then the speaker could exist maxim (at the moment of death itself?) that she could no longer physically see in order to find her way forward into the next world. Consider the more everyday phrase, 'I tin't practice right for doing wrong': Dickinson's last line might be analysed as a cryptic variation on that expression.

Flies, of form, are associated with death and the dead: they feed on the expressionless. Still the presence of this fly remains puzzling. How should we analyse 'I heard a Wing fizz' in terms of its central image or object: the fly itself? Is this clan between decease and flies feeding on corpses and feces all there is to it, or is it the deliberate juxtaposition of the very small (a common insect) and the very big (death itself) that Dickinson wants us to think about? The question remains open.

Dickinson's rhymes can often seem haphazard: half-rhymes, off-rhymes, words that have only the vaguest sounds in common between them. Yet at that place is a delicate coaction of rhymes in 'I heard a Fly buzz'. 'Room' and 'Storm' in that first stanza are echoed in the following stanza, which has 'firm' and 'Room'; 'died' becomes tautened, or dried out, into 'dry'; in the tertiary stanza, the 'be' that rhymes with 'Fly' calls up the 'Buzz' that is suggested by be(due east), also as the rhyming 'me' and 'run across' in that last stanza. ('Buzz' is also foreshadowed past 'was' in the preceding stanza, with this small verb being retrospectively encouraged to join in the onomatopoeia of 'Fizz'.)

In the last assay, 'I heard a Fly buzz – when I died' is one of Emily Dickinson'due south almost popular poems probably because of its elusiveness, and considering – like many of her dandy poems, and her meditations on death – it raises more than questions than it settles. How do you interpret the fly in this poem?

About Emily Dickinson

Perhaps no other poet has attained such a high reputation after their death that was unknown to them during their lifetime. Born in 1830, Emily Dickinson lived her whole life within the few miles around her hometown of Amherst, Massachusetts. She never married, despite several romantic correspondences, and was better-known equally a gardener than as a poet while she was alive.

However, information technology's not quite true (every bit information technology'due south sometimes declared) that none of Dickinson's poems was published during her own lifetime. A handful – fewer than a dozen of some 1,800 poems she wrote in full – appeared in an 1864 anthology, Drum Beat, published to raise money for Union soldiers fighting in the Ceremonious War. Only it was four years later her death, in 1890, that a book of her poetry would announced before the American public for the first fourth dimension and her posthumous career would brainstorm to take off.

Dickinson nerveless effectually eight hundred of her poems into little manuscript books which she lovingly put together without telling anyone. Her poetry is instantly recognisable for her idiosyncratic employ of dashes in place of other forms of punctuation. She frequently uses the four-line stanza (or quatrain), and, unusually for a nineteenth-century poet, utilises pararhyme or half-rhyme every bit often every bit total rhyme. The epitaph on Emily Dickinson'southward gravestone, composed past the poet herself, features just two words: 'called back'.

If you lot liked this poem, yous might as well enjoy these ten short poems nigh death, and Dickinson's archetype poem near a snake, 'A narrow Young man in the Grass'. If you want to ain all of Dickinson's wonderful poetry in a single book, you can: nosotros recommend the Faber edition of her Complete Poems .

The writer of this commodity, Dr Oliver Tearle, is a literary critic and lecturer in English at Loughborough University. He is the author of, among others,The Hugger-mugger Library: A Book-Lovers' Journey Through Curiosities of History andThe Great State of war, The Waste product State and the Modernist Long Poem.

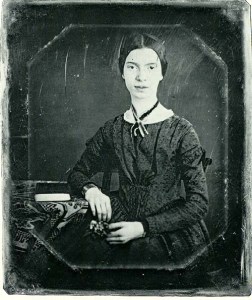

Prototype: Blackness/white photograph of Emily Dickinson by William C. Northward (1846/7), Wikimedia Commons.

Source: https://interestingliterature.com/2016/09/a-short-analysis-of-emily-dickinsons-i-heard-a-fly-buzz-when-i-died/

0 Response to "what do the speaker and those in attendance expect to experience when the last onset occurs"

Enregistrer un commentaire